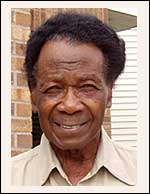

An Interview with Willie Lee Frelix

|

Excerpt from: Voices of Rondo: Oral Histories of Saint Paul’s Historic Black Community Syren Books, September 2005 |

My name is not George.

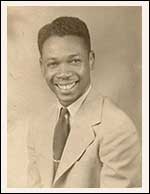

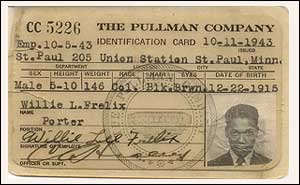

My name is Willie Lee Frelix. [1] I was raised up tough. I started taking care of myself when I was about ten, eleven years old, and I knowed how to survive. Anytime you were raised up back in Mississippi, you could take anything. After I started working for the Pullman Company [2], I had it a little better, especially all during [WWII] war days.

But working for the Pullman Company was a slave-driving outfit. They drove the men.

| Oral Historian |

| Oral Histories |

| Examples of Family Projects |

| Examples of Community Projects |

| Examples of Organization Projects |

| What people are saying about us |

| Contact us |

|

HAND in HAND Productions |

I had an uncle that worked for Pullman as a Porter[3]. He started in 1925 and he told me how it was. They were only getting very little money, like $25 a month. And they had to keep up with everything there was on that car. They come up with a towel or anything short, they would take it out of their $25. Now a lot of people would get off the train, they'd take a towel with them or something like that, and then that porter, he'd have to pay for that towel.

I remember one morning I pulled in Seattle, Washington, and the train stopped, so I get down with my stepping box [4] and put it on the ground and the train moved up about a couple of car-lengths so I grabbed my box and jumped back up in the door.

And when that train stopped he was standing there. I said, "I know he gonna start something."

And when it stopped, it stopped right in front of the boss. You always had a boss out there. They called him a platform man. He met all the trains when they come in. So after I unloaded all my passengers, I got my box put back up, here he comes.

He said, "You are really something. You come in here hanging on the side of the train with your stepping box in your hand. You know better than that." You know what I did? I jumped all over him. When I'm right, don't nobody tell me that I'm wrong. I told him, "You listen. My word is just as good as yours. Now you seen what happened. I seen you standing down there in the first place. The train stopped. I thought it was where it was gonna be. That's all I had time to do is to get my box and step back up in there. Now, you just remember this. Write whatever you wanna write. You just remember my word is just as good as yours." He wrote down everything that I said.

He said, "You are really something. You come in here hanging on the side of the train with your stepping box in your hand. You know better than that." You know what I did? I jumped all over him. When I'm right, don't nobody tell me that I'm wrong. I told him, "You listen. My word is just as good as yours. Now you seen what happened. I seen you standing down there in the first place. The train stopped. I thought it was where it was gonna be. That's all I had time to do is to get my box and step back up in there. Now, you just remember this. Write whatever you wanna write. You just remember my word is just as good as yours." He wrote down everything that I said.

You pretty much walked all the way from Seattle on a nonstop. We were on our feet, walking back and forth between cars and taking care of passengers during the whole trip to Seattle.

Now in the olden days they would have called me in, but at this time we had a union.[5] If they called  me in, they'd have to pay me. They would always wait when I was getting paid to ask me about it. So the next time I was going down, the boss come down to the train. I told him exactly what happened. But that just was the way they were, just a slave-drivin' bunch that Pullman Company. It was just terrible. And all the railroad jobs I under-stand for Black folks it was the same way. But working for the Pullman Company was quite educational. I got to go all over the country. I run on practically every railroad there was in the United States and Canada.

me in, they'd have to pay me. They would always wait when I was getting paid to ask me about it. So the next time I was going down, the boss come down to the train. I told him exactly what happened. But that just was the way they were, just a slave-drivin' bunch that Pullman Company. It was just terrible. And all the railroad jobs I under-stand for Black folks it was the same way. But working for the Pullman Company was quite educational. I got to go all over the country. I run on practically every railroad there was in the United States and Canada.

I wanted to be a Pullman Porter because I wanted to go all over the country. The waiters, they only run on one railroad, like from here to Seattle or Chicago or someplace like that. But being a porter, the Pullman cars would transfer to different railroads and went a lot further. I could get to see all of Canada and Mexico and the United States. So I seen it all.

I had the most fun trips during war days. We went as far as you could go by land, we went up to-oh,  boy, I can't think of the name. It was about 1,000 miles north of Winnipeg. We went up there in August. When I left here, it was real hot and by the time we got there it was about 3:00 in the morning and it was still light outside. It just had got just kind of gloomy looking. It was in August and oh, it was cold. But I got a kick out of that just got gloomy looking for maybe an hour and then it was right back daylight again. That was a lot of fun.

boy, I can't think of the name. It was about 1,000 miles north of Winnipeg. We went up there in August. When I left here, it was real hot and by the time we got there it was about 3:00 in the morning and it was still light outside. It just had got just kind of gloomy looking. It was in August and oh, it was cold. But I got a kick out of that just got gloomy looking for maybe an hour and then it was right back daylight again. That was a lot of fun.

As a porter I took care of one car. We had to keep the car clean all the time. Actually, you wasn't nothing but an inside hobo. Only thing about it, you was inside all the time. At night after 10:00 you would have two cars until 2:00. I would go to bed at 2:00 and get up at 6:00. You'd get four hours sleep a night. Then the porter from the other car would cover my car until I got up at 6:00. So at night you had two cars to watch. You had a connection between two cars. If somebody rang in the other car, they rang the bell in your car and you go look on your meter. It wasn't your car, you had to go to the next car and answer that call. And if you had somebody to put off during the night, you would have to do that. At 6:00 you'd get up, shine shoes or do whatever. You had to shine all the shoes on the train. You'd either do it before or else after 6:00.

You were always assigned to a bed. You were assigned to an upper berth in the back of the car. That's where you slept your four hours every night. Unless if something happened and you didn't get no rest, they'd have to sign your book for no rest. Your boss would or the conductor on the train would sign it. There was some nights you wasn't able to get in a rest.

When I began I made about forty or forty-three cents an hour. I started out at $113 a month. We had a union when I first started. The pay wasn't no good, but you made a lot of money in tips when I first started and that's what I loved. The soldiers would tip you real good. Sometimes when I'd get back home, I'd have $60, $70, or $100 when I got back home, according to how long I was gone. And if I got on a passenger train, made a round trip to Seattle, you'd be gone about a week. Well, you made good tips from the passengers then. Everybody would tip you. Maybe one person from here to Seattle would give you $5.

Seventeen years later I was getting $350 a month and that was hard to live on, 'cause you wasn't making any tips at that time. All the tips was cut off. I would run from here to Seattle at that time on the club car. You didn't make any tips. The company started advocating, "We have raised their salary. You don't have to tip the porter." Now the company did that. You couldn't live on no $350. You were just starving to death.

Yeah. Some of the passengers was real nice and some of them wasn't. I remember one time that I was running from here to Vancouver, B.C., and they had a washout of a bridge. We set in on place for better than forty-eight hours. So we run out of everything. The cars were getting to run out of food, we run out of linen, couldn't make down the beds every night. After we all run out of linen, we tell the passengers, "I can't change your bed. You'll have to sleep on the same linen, but anything else that I can help you out with I'm at your service."

I had another gentleman one day. Everybody on the train had this old way of calling the porters George. They had a way of calling you, "Hey George, so-and-so." George this and George that. At each end of the car you had a place to put your name so everybody would know your name. So I asked a gentleman one day, I says, "How would you like for somebody just come up and call you George? How would you like for somebody to walk up to you and just give you a name?" He said, "I wouldn't like it." I said, "What a nerve you got. You gonna walk up and just give me a name, and you're gonna tell me that you wouldn't like for somebody to do you like that." So I got him real good about that. I don't know why some of the men allowed themselves to be called George, but I always set people straight and we got along just great. But there was really some mean ones.

And I know there was nobody working for the Pullman Company no greater than I was. I was number one. I had a perfect record when I started, and I had a perfect record when I stopped after seventeen years. I got to be a conductor. I got to be a bartender. I got to be everything there was about the railroad. I could sell tickets. I did everything. I learned it all while I was working for Pullman Company.

Being a porter was really an upgrade job for a Black man at that time. It had its ups and it had its downs, but I really loved that job.

1. Willie Lee Frelix was born in 1915.

2. The Pullman Company was founded by George Pullman right after the Civil War and provided a standard for luxurious travel. Beginning in 1867, the earliest staff were the genteel servants of the plantation South. The early porter worked receiving passengers, carrying their luggage and making up their rooms, serving beverages and food, keeping the guests happy, and making themselves available at all hours of the day or night. In Saint Paul, the Pullman Company was located at 214 Fourth Street.

3. Pullman Porters worked for the Pullman Company and carried baggage only for Pullman sleeping car passengers. The Pullman sleeping cars would be transferred between railroads and traveled all over the country.

4. A stepping box was a wooden box to help passengers step between the high train car and the platform.

5. The Brotherhood of Sleeping Car Porters union was founded under the direction of A. Philip Randolph. By 1925, the generation of freeborn Black employees were not as accepting of the poor treatment and low wages as their slave-born predecessors had been. Randolph had many challenges and lack of support from the White union. Against all odds and with the support of many brothers, this Black-controlled union came into existence. In 1978 the Black union merged with the larger union, the Brotherhood of Railway and Airline Clerks.

Willie Lee Frelix was with the Pullman Company from 1942 to 1957, Steinberg Construction from 1958 to 1969, Total Asphalt from 1970 to 1979, and worked as a guard for Business Security Guard from 1985 to 1995, when he retired. He has always had extra part-time jobs to support his family's needs. Willie's family always came first, and though he has had a challenging life, he always worked hard to support and has enjoyed his children. He is the proud father of Clifford, Harold, William, Marion, Charles, Johnny, and Stanley.

© 2024 HAND in HAND Productions